The No List

From the day we opened our doors in September 1980, steadfast and selective have underpinned the attitude behind the standards of the products we sell — and love. When we review ingredients, we consider the interconnected effects of the way that food is processed and regulated by authorities in the U.S., UK, Canada and beyond. All of this happens before hitting our shelves and ultimately your plate. It can be a difficult process, and the answers are not always easy, but we know our food ingredient standards have influenced the way food is grown, raised, processed and experienced around the world.

“The reason it would be difficult for an established company to do what Solely does is because it would have to change their whole supply structure. A regular company would have to change their paradigm – it’s not just a formulation with some inputs. It’s a living thing.”

Simón Sacal, CEO of Solely, Inc

Simplicity Isn’t Easy: An Interview with Simón Sacal, CEO of Solely, Inc

One of Whole Foods Market’s 2020 Suppliers of the Year, Solely makes innovative fruit jerkies and other dried fruit products

Whole Story: OK, Simón, so tell us, who are you and what do you do?

Simón Sacal: I’m Simón Sacal. I’m the CEO of Solely.

WS: What is the quick history of Solely? How did you get to today?

SS: So, there’s no quick history of Solely because we’ve been doing this for 20 years. It’s a family company, and it’s grown a lot, but we started by with the goal of developing technologies fat-free potato chips 20 years ago, and then we started working with institutional businesses and lunchboxes. And, so, the government had a problem in how to give fruit to children at their schools because in Mexico, at some schools, you don’t have roads to get there, refrigerating systems, or even running water.

SS: They came to us because we were working with them on different projects, and they knew we had this technology. We ended up developing a food technology to get an apple and compress it into a little bar. So, it added an option because now the apple was shelf stable.

SS: We started with Solely in around 2016, and it was a very different fruit bar because it had all the smell and taste and color of a regular fruit. And we started in a coffee chain. We made a small test that was very successful in Mexico. And we did some tests here as well in Northern California.

SS: And then we re-engineered the product. We converted it into a fruit jerky. I personally moved to San Diego three years ago to launch Solely, and the first time we sold the product, it was to 365 by Whole Foods Market. It was, I think, 10 stores in September 2018, and we started with the fruit jerky only.

WS: Let’s talk about the idea of vertical integration. Why did you need that 20-year process to get to where you are now where you can bring Solely to market?

SS: We work very close to the farmers to help them certify their plants or their crops organic, and especially to help them plan their crops because we can get all their A product, which is the table-perfect product or the “pretty produce”.

But we can also buy their “ugly” produce, and that gives the farmers a huge marginal advantage because, if not, they don’t sell that part. So, they can plan their crops better, and they work with us, and they get certified. And that gives us a huge opportunity because the only thing we’re adding to our products are the fruits and vegetables themselves. So, one efficient way to do that is working directly with them to get the fruit for Solely. So, that’s the first part.

SS: The second part is once you get the fruit, you cannot put it into a regular process. There’s no one doing what we’re doing. The challenge after that is how to manufacture the product. You have the product. You have the technology. But no one can do this for you, so you have to build a plant, and do the manufacturing yourself. So, that was a huge thing; you have to scale the technologies to get them there. Right now, we have two manufacturing facilities in Mexico, and one in Costa Rica, and they’re big facilities.

SS: We have around 1,300 people working with us in the whole chain directly with our company. And the only way to have Solely bring the products that we have is by having all this infrastructure that we’ve built because there’s no other way to have a product with very few ingredients if you don’t control the ingredients, the process, and the manufacturing. Not only that, you also have to be able to create a volume and scale to get to the prices, and to get to the quality control, and the GSFSI1-certified facilities, etc., etc. So, Solely’s fairly new but it’s taken 20 years of building that infrastructure just to create this disruptive product.

WS: It’s kind of counterintuitive, right, because the marketing of the product is like it’s just one, two or three ingredients. It’s counterintuitive that to have the simplest product possible, you have to have this incredibly complicated development over 20 years.

SS: It is very counterintuitive because it’s a lot easier to make a 25-ingredient granola bar – you go and buy the flour and the sugar, the machines are already there, and the supply chain is already built. To make a product with just a few ingredients, it sounds easy but it’s much more complex because you need all this infrastructure just to make it happen. But, in the end, it’s very rewarding to us and to the consumer.

WS: Could you describe for me the challenge for an existing food company to try to upend their production and start making something like this product?

SS: So, the reason it would be difficult for an established company to do what Solely does is because it would have to change their whole supply structure. We don’t go and buy flour and sugar, and then make a product out of a machine that you buy from Germany. It’s a completely different process where you have to go and source the fruit. Every fruit jerky, every mango fruit jerky, for example, comes from one whole mango. A regular company would have to change their paradigm – it’s not just a formulation with some inputs. It’s a living thing. So, that changes everything.

SS: I’ll give you an example of trying to make something like Solely. So, a regular company would have a very good idea for a new formulation. First do the formulation, and the marketing idea. And then they have to go to a supplier to manufacture that product. The supplier would say, this is what we need; we need to have a vehicle, which is a flour or a granola or nuts, and we must have a binder, which must be a type of sugar or a pectin, and then we can include some nutritional product. That is bound by available technology and sourcing. The manufacturer will not be able to bring fresh fruit into the process. The ingredients must be something that’s already on the market. In order to make something really disruptive and new, you would have to change the process completely. It couldn’t be done by a third party. And even if it could, the product would be so expensive that it would be very, very niche. It’s impossible to do it massively because you need to be able to source huge amounts, and to process huge amounts, and to have all these quality controls and certifications. And the only way that we’ve found to do that is to build it. That’s why it took 20 years.

WS: How has the technical innovation that you guys started with and pursued all along, how has that enabled you to create a disruptive product?

SS: We’ve been very innovative technology-wise, and it has been forced upon us because we come to a crossroads where you either stick to what is known or you go on to a new path. So, we’ve chosen the new path, sometimes successfully, sometimes not. Early on in our career, we understood that it’s not impossible to create new things and new technologies. It’s a matter of having the right team, understanding the science behind it, and trying new things. It’s been interesting finding out that there’s so many things that have never been tried. I feel that most of the food industry relies on very basic technologies such as, extrusion or baking, and then they have very high technology to do that. But new processes are not created very often because it’s just too expensive to go there. That’s why real profound innovation is not done every day. It’s uncomfortable.

WS: How is Solely going to change the industry?

SS: So, Solely’s changing the industry, first of all, by showing everyone that it’s possible to bring, products that are indulgent and that are affordably priced to the market. And I think that alone will bring more innovation that way, and we welcome it. We want to help more farmers, and bring more alternatives to consumers, and we’re all for it. We’re all in for that. It also shows the consumer that there are alternatives, that it’s not only the marketing and the label that says it, that there are alternatives that taste good. And that changes everything because it takes them back to the roots of what’s growing in the ground, and it takes them back to products that are wholesome – it’s a huge change.

WS: How has Whole Foods Market helped you to build this new business, helped you to advance this idea?

SS: Whole Foods Market has been a very, very important relationship for Solely. Their help and involvement have been valuable to the development of the brand. People in Whole Foods Market are different from people in the larger system because they understand the impact that we’re trying to make in the farming community, globally with climate change and the Earth, and with our own people. We couldn’t get where we are without Whole Foods Market.

WS: It’s easy to underestimate the scale of waste that goes on behind the scenes in the food industry. What sounds like a tiny percentage change on the back end, and how much of the full crop you’re utilizing, it actually could snowball into huge effects behind the scenes.

SS: Food waste is a huge problem worldwide. People don’t realize how big it is because when you have a crop, the farmer is never able to sell 100% of the crop, because some percentage of the whole won’t be “pretty” enough for the shelf. We can buy everything, and we can use everything with them. That reflects a huge difference for their livelihood, and it’s perfect for us as well because we can control the quality of the product getting in. It’s a huge difference in terms of environmental impact because you have the same resources, the same land, the same amount of water, but much more useable fruit.

WS: How does the larger food system incentivize these inefficiencies?

SS: I think the larger system incentivized cheaper labor and the sourcing of the products, and by aligning everything with profit, and training the consumer to always ask for something that is not possible naturally.

So if I want to have, you know, mango all the time I must work with the whole world food supply because there’s a seasonality for mango in Latin America, so I have to go to Asia. If I want the product to be extremely sweet I have to add more sugar. If the consumer understands that getting a better product means you have to refrigerate the product, to take care of the product or have some flavor sometimes and other flavors other times and have more variations of the flavors and the textures I think that’s one part of it. The other is that small decisions that are made on a global scale can affect the consumer and the food system in a very deep way.

Changing our Minds – When Ingredients Change Status

The Whole Foods Market Quality Standards Team maintains an ingredient list of acceptable and unacceptable ingredients for food, supplements, body care and household cleaning products. It’s a living list. We continually review new and novel ingredients brought to us by our buyers, product developers and suppliers. We also monitor ingredients already on our lists and consider whether their current status should stay the same. And occasionally, we change our minds.

How does that happen and why? In the case of our ingredient standards, it often means learning of new research about an ingredient, or a passionate buyer or supplier asking us to reconsider status. While ingredients we’ve marked as unacceptable sometimes become acceptable, the more common story is a status change from acceptable to unacceptable.

When an ingredient is being evaluated for a possible change from acceptable to unacceptable, we consider a variety of factors. Are there available alternatives to the ingredient? How long will suppliers need to reformulate, retest and relabel? Would the change result in withdrawing a significant number of products from our stores, affecting shoppers? As you can imagine, the answers vary from case-to-case, but here are two examples of significant changes that we are proud of.

Partially Hydrogenated Oils

While naturally occurring trans fats are found in small quantities in animal fats, artificial trans fats are created when vegetable oils are partially hydrogenated, making them solid at room temperature. They offered an affordable, shelf-stable alternative to animal fats while creating the same mouthfeel in finished products. But in the late 1990s, reputable research emerged indicating negative impacts to cardiovascular health from ingesting hydrogenated fats. We knew we needed to reconsider their acceptable ingredient status at Whole Foods Market.

After working with our buyers and suppliers on timelines, we prohibited hydrogenated fats – both partially and fully hydrogenated – in food and supplements. And all products containing them were removed from our shelves as of 2003. We allowed them to remain in body care (except lip products) because topical use was not connected to health effects. The FDA banned partially hydrogenated oils in 2015, twelve years after we did, with a deadline for compliance in 2018.

Oxybenzone and Octinoxate

We have long offered both chemical and physical sunscreens on our shelves. Chemical sunscreens are absorbed into the skin and are no longer visible once applied. Physical sunscreens sit on top of the skin, forming a white layer that reflects the sun rays.

Several years ago, we began to see research on certain chemical sunscreens being linked to potential harm for both human and environmental health. We worked with our suppliers who had products with chemical sunscreen ingredients on our shelves, and went forward with a plan to prohibit two of those ingredients: oxybenzone and octinoxate. Oxybenzone was added to our unacceptable list in 2017. We allowed a longer runway for octinoxate which we labeled unacceptable and products were removed from stores by 2019. In 2018, the state of Hawaii announced it would ban sunscreen with those same ingredients from being sold in the state. Other cities and countries have now adopted that ban.

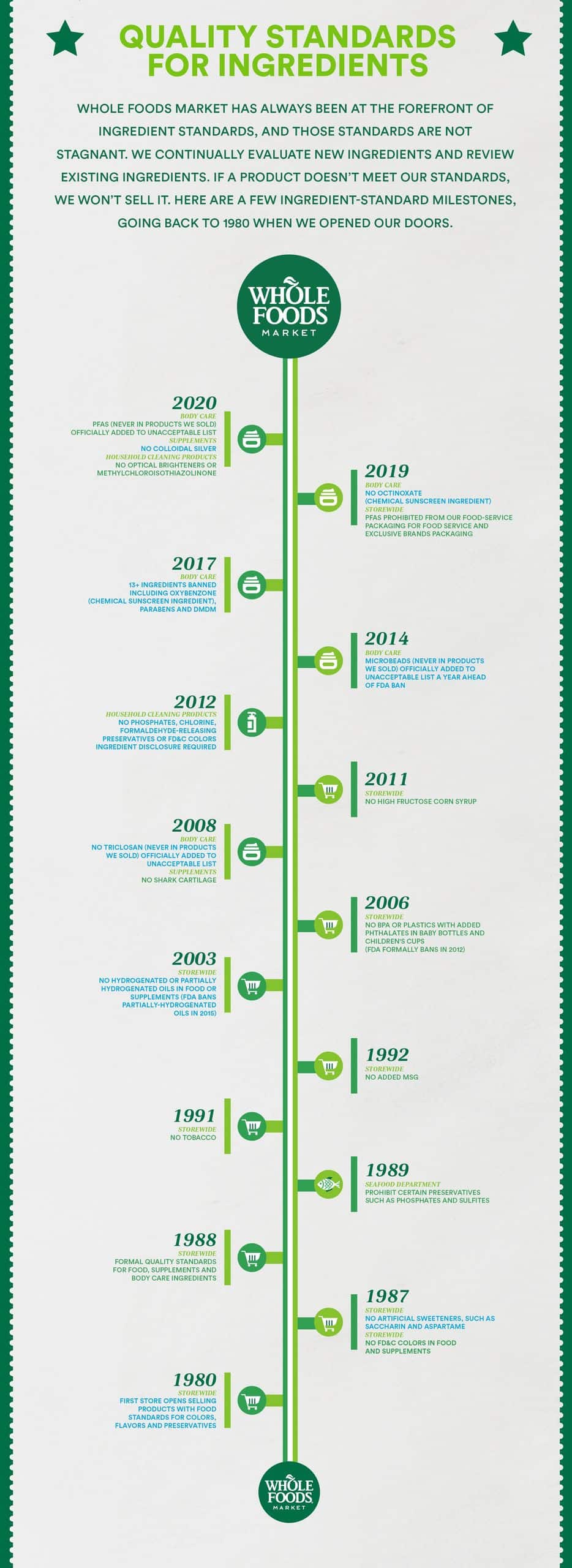

The No List Timeline

How We Work: Ingredient Standards

The cornerstone of our Quality Standards are our acceptable/unacceptable ingredients lists for food, body care, supplements and household cleaning products. In order to be sold in our stores, products must contain only acceptable ingredients that have been reviewed for that specific product category. The Quality Standards team is here to share a little history about how our food ingredient list came to be, and how we continue to work on reviewing ingredients day in and day out.

When Whole Foods Market opened in 1980, our founders knew they wanted to upend the norms of both the natural food industry and the conventional American supermarket by bringing them together. This meant that from the very beginning, Whole Foods Market had to have standards for what it would and wouldn’t sell.

Those early days were focused on what we would not sell in our stores, with the identification of food additives we didn’t want in products on our shelves. The very first unacceptable-ingredients lists were handwritten by one of our original Whole Foods Market Team Members, Margaret Wittenberg, who served as our Global Vice President of Quality Standards until her retirement in 2016. Over time, as new ingredients entered the market, we also had to begin considering what we would allow in food, and our list evolved to include both acceptable and unacceptable food ingredients. We followed this up with ingredient standards for body care, supplements and household cleaning products.

As the food industry continues to change rapidly, we receive new ingredient requests almost every day, and we have to make decisions on which of those ingredients are acceptable or unacceptable. So, how do we decide? We look to a wide variety of sources and experts to find the answers to a few important questions:

What is the ingredient?

First, we look at the ingredient itself. What is it? What is its purpose? Does it have a long history of use or is it brand new in products on the market? Is it being used in other categories in our stores?

We start with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Of course, just because the FDA allows it doesn’t mean we will (think of FD&C colors, which we’ve banned from the beginning!). And just because we allow an ingredient in one category in our store, doesn’t mean we believe it should be acceptable in all categories. For example, we don’t allow hydrogenated fats in food and supplements, but we do allow them in body care, which is not ingested. There are many herbs we allow in supplements that we ban from food and beverages.

Next, we look at decisions by other regulatory bodies like those in the European Union, Health Canada and United Nations. And we dig into scientific and medical studies, food science texts, herbal handbooks, cosmetic chemistry, culinary resources and more.

Is it necessary?

This is a question we ask ourselves, and our suppliers, a lot! For example, we don’t allow bleached flour. Bleached flour is treated with chemical bleaching agents to speed up the flour-aging process, which will happen on its own naturally. We’ve long felt that treating flour with bleaching agents is unnecessary and that our suppliers can produce high- quality baked goods without it.

Are there higher quality alternatives?

A supplier approached us about an emulsifier called polyglycerol polyricinoleate (PGPR) for use in a chocolate candy coating. If you looked, you might have seen it in candy in your kids’ trick-or-treat bag. After researching, we determined the ingredient would be unacceptable. It is highly processed and unnecessary because higher- quality alternatives exist, like sunflower or soy lecithin.

Is it compatible with our Core Values?

It’s important to us that all the decisions we make take our Core Values into consideration. Does this align with selling the highest quality natural and organic foods? Would our decision be too difficult for suppliers to achieve? And above all, would our customers expect to find this on our shelves?

Today, Whole Foods Market bans 230+ food ingredients, 115+ supplement ingredients, 180+ body care ingredients and 120+ household cleaning product ingredients commonly found in other stores. Creating and evolving our ingredients standards is part science and part art and the answers are not always easy. But we know our ingredient standards are part of how Whole Foods Market has influenced the way food is grown, raised, processed and experienced around the world. We’re proud of our legacy and will continue to lead the charge when it comes to bringing high-quality products to our customers.

The No List In Action